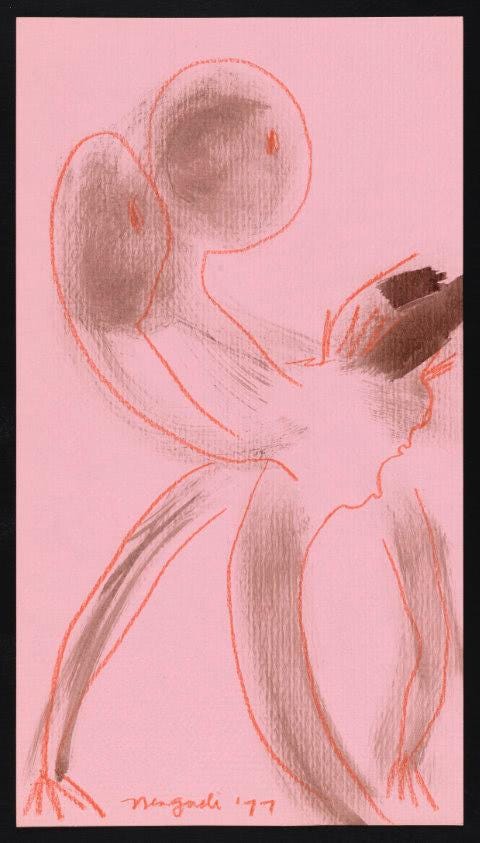

Baby fever

This summer, my sister is having a baby, which means that for the first time, I will be an aunt. The idea of a generation after me, which feels abstractly represented to me right now, will come sharply into focus. In this moment of heightened pessimism, it makes me feel optimistic that the world goes on, that people will keep being born and dying and making the best of what they have. I am excited to meet this baby, to watch it become a person.

Still, I have wondered over past months what kind of world this child will grow up to inherit. It will undoubtedly be almost unrecognizably different than the world in which I grew up. This is true for almost every generation in some way. It is a common form of malaise that tends towards conservatism. But the government services, career trajectories, civil rights, and global economic dynamics that shaped the world in which I grew up have been rapidly unwinding over the course of my lifetime. I grew up in a leaner America than my parents did. By the time I was seven, I had fewer rights to speech, to privacy, to gathering, to collective action, to travel, to imagine a different future.

Birth rates are ostensibly on the decline. More women in their 30s currently give birth in America than women in their 20s. Hispanic women give birth the most, followed by Black women, with white women third (these demographics are drawn from aggregated US government data and therefore necessarily limited). Much has been made of these two statistics. The first seems to represent a historical demographical shift, a kind of triumph of suffragism or a total corruption of the function of womanhood, depending on who you ask. The second has stoked the phantom fear of “replacement,” otherwise styled as white genocide. Our decadent enlightenment of civil rights and secularism, so acolytes of this story such as Vice President J.D. Vance would tell you, has been so fully accomplished that it has succeeded in devastating the settler population of the United States. In a short generation from now, they will be eclipsed.

It has proved to be nearly impossible to reverse this trend. Gideon Lewis-Kraus wrote a long, bemused essay in The New Yorker in February about the apparent futility of pro-natalist measures. Although governments from Korea to Finland have attempted welfare policies to encourage their population to reproduce and although others, such as Hungary and Russia have made it a matter of oppressive patriotism, none have succeeded. “The only overarching explanation for the global fertility decline,” concludes Lewis-Kraus, “is that once childbearing is no longer seen as something special—as an obligation to God, to one’s ancestors, or to the future—people will do less of it.” Similarly, Elizabeth Bruenig in a recent Atlantic article on the subject writes that “if you believe the human race should have a future, you’re pronatalist with respect to somebody.”

Bruenig, a true proponent of the traditional male breadwinner Fordist family, proposes giving money, tax credits, and other welfare incentives to young people to entice them to start families. She throws out a challenge to the Trump administration, noting that since the ostensibly pro-family right now has power in the government, they are free to instate such policies anytime. Instead, in their first few months in office, Trump’s government has aimed at slashing social welfare programs from Medicaid, food assistance programs, and social security to student loan relief, libraries, and labor protections (which often include parental leave policies). They have also crashed the stock market and belligerently alienated America’s traditional allies, raising looming fears of recession, mass layoffs, war, and other kinds of terrifying and uncertain futures. If this administration intends to raise the birth rate, it seems fairly clear they propose to do it by fear and intimidation rather than by reconstructing a paternalistic social safety net. In recent weeks, Kansas legislators overrode a veto to push through a new bit of pronatalist law, enabling pregnant women to seek child support payments from the moment of conception.

The bill has mainly been interpreted as an attempt to push through a new basis for fetal personhood, but it is also consistent with the historical structure of Anglo-American welfare systems, which often focused above all on the punishing of non-normative family arrangements. In Family Values, Melinda Cooper describes how aggressive child support laws were introduced at various historical moments in history in order to reduce the dependence of women and children on government aid and to force working-class men to participate in the labor force. Until it was outlawed in 1969, unmarried or widowed women with dependent children in the United States could be denied welfare benefits if they were having a sexual relationship with another man, who was then by default held responsible for supporting them. In the 1990s, as a part of Bill Clinton’s massive welfare reform program, states were required to divert much of their family welfare benefits to tracking down and penalizing biological fathers in order to force them to pay child support and to sanctioning women who refused to name or help with the search for said fathers. “By diverting a substantial portion of the federal welfare budget to the task of extracting child support from fathers,” writes Cooper, “welfare reform served to remind women that an individual man, not the state, was ultimately responsible for their economic security.”

It is a strange time to be pregnant. Natalism is on the rise, preached from the pulpit of the White House. Pregnancy-related deaths increased 27% between 2018 and 2022, particularly among Black and Native American people. Multiple states have disbanded their maternal mortality committees or suppressed their findings. Rates of sepsis associated with miscarriage almost doubled in Texas after the state’s near total abortion ban in 2021. Recent cuts to scientific and medical research programs threaten to set back efforts to make childbearing safer. News stories have proliferated about people arrested and prosecuted for miscarriages or left to bleed out in hospital beds rather than administered abortion care.

This violent disregard and even contempt for the lives and health of pregnant people seems contradictory at a glance to the radical pronatalism espoused by a loose coalition of Christian conservative nationalists and paranoid libertarian feudalists. It is perhaps strange that no one committed to banning abortions seems particularly concerned with the problem of making childbirth safer. This paradox is partly because abortion has been so successfully boxed into a moral-religious framework which compares abortion variously to mass disenfranchisement, chattel slavery, genocide. Fetal personhood is the most persistent node in this framing. If an in-utero embryo is a human like any other, you are necessarily obligated to recognize its positive rights and civil liberties. This framework also inevitably pits the carrier of the fetus against the fetus itself in a kind of zero-sum gestation war. The fetus’s right to life must prevail even in the case of an ectopic pregnancy, where there is no life present, or of a nonviable pregnancy which cannot survive outside the womb. If the pregnant person dies, these pregnancies will also inevitably cease to be, but the symbiosis of their relationship is concealed by this philosophical battle for existence.

Melinda Cooper locates the shift towards this framework within the context of the broader liberalization of the United States. While early 20th century American abortion activism was often associated with middle-class eugenicist figureheads like Margaret Sanger, who were interested in family planning as a matter of social hygiene and (in her telling) largely supported by mainstream Protestants, its adoption in the ‘60s by advocates of sexual liberation, feminism, and social democratic welfare policies gave rise to a newly fervent anti-abortion Evangelical right, who were drafted into the “New” Reaganist right coalition. “What united them was a shared hostility to the new jurisprudence of privacy, which they understood as creating a positive constitutional right to sexual freedom. [...] they feared that the right to sexual privacy would have dramatic transformative effects on the public life of the nation, and as such should be opposed at all costs.”

It is impossible then to dislocate abortion from the nexus of the traditional family. Even many of abortion’s ostensible supporters on the left are squeamish about its real implications. It is not uncommon to hear arguments about how you should have the means to support a child before having one and about being at a point in your life where you are unable to mother well, or feel good stories about having an abortion when you were young and unstable and then going on later in life to form a traditional two-parent household with wanted and well-loved children.

To be clear, all of these reasons are valid reasons to have an abortion, and in a landscape of ever-shrinking abortion access, their validity often needs defending. But the choice to couch abortion in indirect terminology, to deny its real radicalism and potential to disrupt the normative structures of the heterosexual family, and to yield to the framework of the right has been nothing short of disastrous for the understanding of abortion in America. If you implicitly portray abortion as a necessarily evil, as a bad thing that must happen for the cause of personal self-determination or “choice,” if you restrict it to the domestic realm of “privacy,” you can only cede ground from there. “[T]he distinction between making fetuses killable and making it easy and stigma-free for people to take the decision to kill a fetus,” wrote Sophie Lewis in The Nation in 2022 after Roe v. Wade was overturned, “is significant. The former refers to casting something (a lab rat, for example) out of the sphere of the grievable, thanks to a tidy and final verdict on the permissibility of systematically sacrificing its life to a greater cause. The latter, while expanding access to the means of feticide, does not necessarily require any such sanitization of violence.”

This sanitization of violence, argues Lewis, also sanitizes the real brutality of gestation. Welfare will never be a sufficient measure to compensate people for forced gestation. There is no amount of tax credits or baby boxes or parental leave or food assistance that could offset such an intimate violation. Nor is abortion really a matter of privacy, neatly tucked away to enable us to keep living our respectable public lives. Instead, it exposes the seams in the reproductive labor system, how grotesque and unchallenged the business of childbearing and childrearing is. By tucking abortion away, as Lewis points out in a searing critique of The Handmaid’s Tale in her brilliant manifesto Full Surrogacy Now, we have also relegated it back to the eugenicist realm, to the idea that population control is an ugly business but needed to keep the surplus population in check.

Pronatalist welfare ideas tend to conceal similar ideological roots to the right-wing conspiracy theories of poor women of color or immigrant women having babies to become eligible for government support (“welfare queens” and “anchor babies”). Liberal pronatalism tends to obfuscate its core discomfort with the denaturalizing of gestation. Gideon Lewis-Kraus in his New Yorker essay referenced above acknowledges the dehumanizing stakes of natalism, but goes on to question the bankrupt ethics of a society that “weighs children against expensive dinners or vacations to Venice—as matters of mere preference in a logic of consumption.”

If Lewis-Kraus, like Anastasia Berg and Rachel Wiseman who recently published a much debated book called What Are Children For?, limits his analysis of reproductive choice to the upper middle classes — those who might legitimately be choosing between a vacation-filled lifestyle and a baby — this is consistent with his rhetorical argument. He claims that fertility rates are sub-replacement nearly everywhere in the world and only mentions in one throwaway sentence, bracketed off by em-dashes, that there are notable exceptions in Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. He does not treat these places as worthy of further analysis, focused as he is on the idea of children as faltering investments for the global rich. But Jason Smith, in a long and dense essay for The Brooklyn Rail on demographics, focuses almost entirely on those places where the population is rising and where the high birth rate coupled with a rapidly rising standard of living has created an exploding youth population. Smith attributes this phenomenon to an economic transitional phase of semi-proletarianization: that is, a society that is no longer agrarian but where much of the population has no consistent access to stable waged labor. In such an informal economy, children are more of an economic guarantee than an economic investment since they are also able to bring in income as soon as they reach adolescence. “In 1900,” writes Smith, “just nine percent of the world’s population was African. By 2100, two in five humans will live on the continent.”

It is startling that such a massive demographic shift goes so unacknowledged by liberal commentators. The liberal enthusiasm for natalism is instead variously expressed as musings about what we were put on earth to do (about choice, in other words) or as a project of individualism subsumed to the economic collective. Underlying the dream of a free market, be it libertarian or social democratic, is the root structure of the family, resilient enough to absorb care, unpaid gestational and reproductive labor, and the expenses of raising, feeding, educating, and training the next generation in the ethos of work. Lewis-Kraus invokes a dreary vision of wealthy nations treating their children as human capital, conditioned to study long hours at prestigious schools, to gain rarefied skills and talents, to fill out their resumes early on, and to endlessly war for opportunities in an embattled elite ecosystem, while their parents funnel hundreds of thousands of dollars into college and retirement funds or various kinds of trusts. All this stands against a backdrop, as Kiara Barrow pointed out in a sharp essay for The Drift on the asset economy, of soaring wealth inequality, one where income is increasingly eclipsed by inheritance as a metric for how your life will turn out.

There is a tension then between natalism, an ideology to renaturalize the business of having children and to return it to the sanctified domestic sphere, and the looming fear of downward mobility that infects the American middle class. You wish to have a child who will be extraordinary, who will live a sheltered and precious existence, who will die richer than she came into the world. Your desire for a child is thoughtful and responsible. It takes into account all the different strains of sociopolitical theory around childbearing: climate change, resource scarcity, growing illiberalism, demographic decline. Your child will be loved. This project of reproduction has nothing in common with the poor, the uneducated, those living far away in vast cities whose names you do not know who continue, perversely, to have children despite their conditions. That the two kinds of reproduction are actually identical in their most basic form, that all gestational labor is brutal and potentially deadly, that you cannot predict or plan for someone else’s life, that children of all social classes are harmed by the world, that poverty and disease and violence seem to be encroaching on America, is the unspeakable truth underpinning natalism — unspeakable because it is painful to its adherents to acknowledge.

What would a radical ethics of gestation and care really look like? What would it mean to totally overhaul our inherited system of reproductive labor and normative nuclear family structures? Feminists puzzled over this in the second half of the 20th century, when the question of reproductive labor seemed somehow easier to question than it is now. In her landmark essay, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” Hortense Spillers rebukes the infamous Moynihan report with its recommendations for how to cure the “pathology” of Black American kinship structures by disciplining them into normative family relationships (a male breadwinner bound to virtuous hard labor to support his dependents). She wonders, movingly, how to denaturalize reproduction away from its economic and gendered hierarchies. Donna Haraway distinguishes between parenting and reproduction, calling the first a practice of caring for future generations, a kind of tending to the earth and its beings, and the second a practice of making more of yourself. This second thing has been variously interpreted, legally and socially, as a process of cellular division and as an ethics of stewardship, responsibility, and accountability. The progression, in the American welfare system, from considering any men involved with a mother to be the de facto legally responsible parent of her children, to holding any biological father of a child financially responsible for its upbringing, to holding the biological father of a fertilized embryo to the same social contract is instructive in how elastic this definition can be.

Sophie Lewis further elasticizes it in her case study of surrogacy. In Full Surrogacy Now, she runs through the incredibly exploitative, racist, and dehumanizing practices of the contemporary paid surrogacy industry which is often offshored, its obsession with the purity of biological parenthood, and its contempt for the surrogate as a vessel. Lewis does not propose to outlaw surrogacy; instead, she proposes to regulate it, even to expand it. Within the practice, she finds a kernel of something radical, an unmaking of the natural relationship we perceive between gestator and fetus or between mother and baby. It contains not only a powerful feminist demand, along the line of Silvia Federici’s Wages Against Housework (“Every miscarriage is a work accident”), but also a radicalizing reframing of labor. In Lewis’s words: “[W]hat if we faced up to the possibility that a far, far wider range of social labors than we might previously have thought is fundamentally akin to gestatedness, gestatingness, miscarriage, abortion? What if we really felt the politics of uterine work to be comparable to other labors?”

This flip, a theory of labor that starts from reproductive labor rather than incorporating it under the aegis of waged capitalist labor, holds remarkable possibility. What could a world look like where pregnant and parenting people were unalienated, unburdened by the naturalization of their work to the domestic sphere? What would it mean to actually cherish and dignify children, not only those biologically or ethnically in proximity to you, but all children? What would a radical ethics of care look like, one in which everyone learned how to parent in the Haraway sense?

People often compare pregnancy to various kinds of intellectual work, for creative and artistic production, for thinking and writing, and I have always found this arrogant and solipsistic. Gestation is not a labor of the mind. It is risky, bloody, profoundly intimate, potentially deadly. It is a process of giving salts and blood and cells and nutrition to bind together something that will become a human. It seems to re-relegate it to the home to compare it to intellectual work. But it is useful perhaps in trying to understand how it is and is not like other kinds of labor. Of course, it is not exactly like anything else. It is its own sort of work and also like other forms of work just as creative work is. It feels tainting to associate it with money, with labor, like you are losing some essential purity, but that purity is the thing we have to do away with after all, that idea that this is a labor of love, that it is our biological destiny, that it used to be as natural as breathing, and that only modernity has corrupted it.

Abortion then is a node not only to a different vision of reproductive labor, but also to a different vision of what gestation means, one that requires us to confront the messiness of it. If pregnancy is work, then abortion is a voluntary termination of that work. It is ceasing to do the labor that makes a life. That labor, like all other forms of life-saving labor that we practice, must always and invariably be a voluntary contract.

brilliant essay

While I love this article, fathers and low class men are named as the sufferers of child support payment in attempts to shirk federal responsibility, but women are not named, but as “people” when often women in particular are the primary bearers of reproductive coercion. In an attempt for inclusive language, men remain an unchanging, unified class but there is not the same recognition of a class of women?