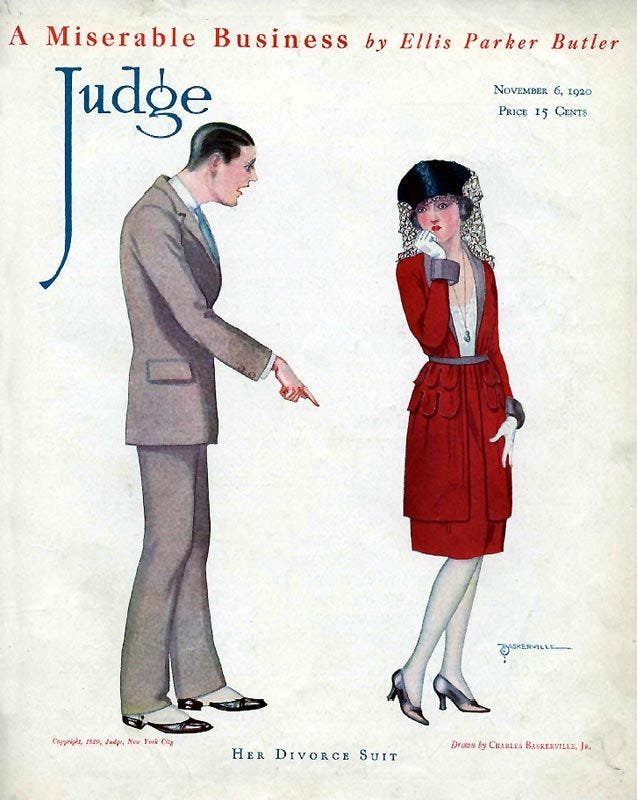

Divorce plot

The first great divorce novel doesn’t actually feature a divorce at all. In Anna Karenina, published in conservative 1870s Russia, the eponymous protagonist begs her older, neglectful husband for a divorce so that she can marry her lover. He refuses. Divorce is scandalous, complicated, and unnecessary, and he is not inclined to grant Anna any favors. In rebellion, she elopes with her lover but their affair is blighted by the complicated legal circumstances, and by her indefinite separation from her son, who she worries she might never see again. Shunned from society and terrified that her lover will abandon her, she jumps in front of a train and dies.

Tolstoy started writing a very different novel, one in which Anna was an unlikable and shameless adultress, and her husband was a sort of victimized saint. The final novel is very different from this original outline. Anna is complex and willful; persecuted by society, yet trapped in a gilded cage that is partly of her own making. She sees where her missteps will lead her but she cannot prevent them. Or maybe it is simply that living as she is, in her cold and loveless marriage, is unbearable.

This was the original contour of the divorce novel and its prototypes: Madame Bovary, Hard Times, Jane Eyre, The Age of Innocence. In these works, marriage is a kind of prison, and escaping from it entails ruinous social and legal consequences. When Ursula Parrott published Ex-Wife in 1929, divorce was commonplace (if still frowned upon), and the protagonist—young, broke, pregnant, and abandoned by her husband for a newer model—wonders if this new world, with its recent liberalization towards marriage, has served women the raw end of the stick. Parrott, like her protagonist, underwent at least four illicit abortions after her early divorce and was blacklisted from the journalism industry by her ex-husband. The heroine of Ex-Wife is freed from the constraints of the stringent social role of wife and mother prescribed in the 19th century, but she is not freed from misogyny. In a 2023 New Yorker review of the novel upon its recent re-release, Jessica Winter diagnosed Parrott with a case of “false consciousness,” pointing out that Parrott seems to believe women had above all won “the freedom to be harmed.”

The afterlife of this idea—that divorce represents a paradoxical setback to the cause of women’s liberation—lingers heavily in the contemporary divorce novel. Rachel Cusk finds the “broken mechanism of feminism” laid bare in the failed marriage of Aftermath. In Liars, Sarah Manguso imagines the woman for whom the protagonist husband leaves her as “a feminist heroine, [...] living for herself alone, grinding her boot into the face of another woman.” The restless main character of Miranda July’s All Fours initiates a fight with her husband, and afterwards muses that “setting up some sort of new, unleashed life as a divorced mom sounded like a punishment, someone else’s story.”

The pessimism of these novels, their persistent narrative arc which describes relationships with men as inevitably rife with drudgery and humiliation, derives in no small part from their boundless optimism about marriage. Perhaps reflecting a generational tilt (July and Manguso were born in the mid 70s and Cusk in the late 60s), marriage is presented as an opportunity for equal partnership, a new and reinvented institution co-opted for a feminist present. The shock of reality then is a specific kind of letdown, a betrayal, not only by the men who were supposed to love them better, but also by the dominant cultural narrative which promised them they could transcend the staid conventionalism of traditional middle class marriage. Manguso wonders if the problem is simply that “men hate women.” In All Fours, a younger woman in her 20s, newly engaged, explains to the unnamed protagonist that “Marriage is a vestige of the slavery mindset, people as property.” She wants to be married to her fiancé for her entire life, an idea she finds romantic, but she also wants to keep having sex with other people, an idea she finds exciting. The protagonist, seemingly on the brink of divorce, has no retort. She too will come to explore something like an open marriage.

But to reduce the oppressive dynamics of marriage to sexual exclusivity is strangely blinkered. Anna Karenina’s tyrannical husband refuses to grant her a divorce, even after she reveals her love affair to him, preferring to maintain a legal stranglehold over her and prevent her from rebuilding her life. The stakes in these contemporary divorce novels are more existential than urgent: they wonder less whether their protagonists should get divorced and more about what the point and purpose of their lives should be in the first place. Their answers to the latter question reveal above all a deep class anxiety, one that is inextricable from the institution of marriage and all its attendant disappointments.

In A Frozen Woman, Annie Ernaux’s 1981 novel about her marriage, divorce is a looming but unrealized cloud on the horizon. In reality, Ernaux separated from her husband, Philippe, after publishing the book, and described it later as a foreshadowing of her divorce. But the marriage it portrays is so staid and miserable, slowly transforming her into the eponymous “frozen woman” that it is hard to imagine it turning out otherwise. It ends on a note of despair. Ernaux imagines a wrinkled face looking back at her, that she will age without even noticing it, moving through her domestic routines as if sleepwalking.

A Frozen Woman opens during Ernaux’s childhood, describing the women she grew up around in her working class Normandy upbringing, almost none of whom were “good fairies of the home” or “mute, submissive women.” Instead, they have “untidy” bodies and loud voices. They barely cook, rarely dust. They work in factories or on farms or in shops that are open all day and come home at night tired like the men. From her mother, Ernaux learns that girls are on equal footing with boys and that they will have to pull their own weight in the world. Her parents are focused on social mobility and they discourage her from marrying too young or devoting her time to housework. The lessons on beauty and docility come later, drummed into her by the romance novels she reads, by her classmates, by her teachers. One of her friends teaches her the right way to dress, the right way to move, the right way to speak, endlessly critiquing in a way that Ernaux is later able to recognize as deep shame. The classmate, like Ernaux, has grown up working class and she is desperate to conceal her roots and to marry up in life. Femininity is mostly a vehicle, in The Frozen Woman, for class mobility.

Ernaux marries well. Her marriage is a modern one. Her husband likes that she is smart and sophisticated, that she has good taste in furniture and in books and that she wants to write and to work. But he also increasingly assumes that she will fulfill the archetypal domestic role and support his intellectual ambitions to the detriment of her own. His own mother is a model of femininity, so sweet and inoffensive it is impossible to imagine her annoying anyone. Ernaux begins to see herself as an “obedient cog in an asepticized, harmonious system that revolves around him.” She cares for the baby so he can play with it at the end of the day. She cleans the apartment so he will come home to it sparkling. She cooks, she brushes his suit. She gets a job teaching and continues to do all the domestic labor when she comes home at night, taking on the duplicate roles expected of modern, progressive women.

Much later, in The Young Man (2022), Ernaux details an affair she had in her 50s with a man in his 20s. She sees signs of her own working class roots in him, in his occasional poor manners, in the lengths to which he goes to save money, and in his apathy about society. She realizes, with a dizzying sense of estrangement from her past self, that their roles have reversed. “With my husband, I had felt like a working-class girl; with A., I was a bourge.”

On its surface, All Fours by Miranda July hits similar notes as The Young Man. Like Ernaux, the unnamed protagonist of All Fours develops an all-consuming obsession with a much younger man named Davey, who works at a Hertz car rental service. His desire reassures her that she is still lithe and fuckable, a fear that plagues the novel. But he also stirs up memories and forces her to confront her younger self. She does not experience the shock of recognition and then of alienation that Ernaux does when she recognizes her lover’s working class roots. Instead, she is both embarrassed and turned on by his lack of sophistication. When Davey tells her he is a dancer, she initially assumes that he must be bad at it. She slyly hires his wife, an interior designer, to remodel the motel room where she is staying. She pays $20,000 for the project, an amount that (she says repeatedly) she earned for writing one sentence, and that Davey has told her he is working overtime to save up. After the remodel, she is surprised to find out that his wife has good taste—unpleasantly surprised, the reader senses.

She does not consummate her relationship with Davey because he wants to stay sexually faithful to his wife. Instead, he pees in front of her and then changes her tampon. Later on, she initiates a meeting with Audra, the older woman who took his virginity years earlier and they end up having sex in a sequence that borders on the grotesque. Although much of the book is threaded around menopause and aging, the protagonist is disgusted by Audra’s body, which is described in graphic terms as overweight and unattractive. Emma Copley Eisenberg succinctly indicts July’s blatant fatphobia, which is clearly bound up here with intense snobbery. The protagonist not only ridicules Audra’s actual physical appearance, but also her sexual desire, which she finds greedy, debased, and unseemly on such an unappealing body. She is jarred even by a fleeting coy expression on Audra’s face, which appears bizarre and incongruous on an older woman. “I made a mental note,” she remarks, “to stop looking coy in the next three to five years.”

Writing for The Drift, Oscar Schwartz diagnosed the contemporary divorce plot as a gender swap, one that borrows all of its beats from mid-century novels about men’s midlife crises. It fails to really break down gender norms, Schwartz argues, because it tends to focus on the same narrow solipsistic questions about freedom and aging as its self-indulgent predecessors: is it possible to be both a wife and an artist? Is it more important to be a good woman or an interesting woman? Can you really work out your issues by having an affair with a younger person?

But gender has a deeper and more pernicious role in July’s book. She experiments self-consciously with gender swapping, both during her experiences with queer sex and in her marriage. These experiments are, however, confined within the tight limits of her social class. Her encounters with other people who do not conform to this—Audra, Davey, and the various service workers who appear in the novel—are punctuated by voyeurism. She is a tourist in their world, dropping $20,000 out of lust and boredom, hooking up with a woman who repulses her just to prove a point. In her real life, she exercises maniacally and obsesses over her desirability and femininity in ways that feel tiredly reminiscent of Ernaux’s high school age classmates. When she and her husband try to reconcile, they do so by roleplaying. She plays herself; he plays a lower class telephotographer who indulges in crudely stereotypical misogyny and dominance in ways that she finds exciting. They play, in other words, not so much with gender or with kink, but with class.

All Fours circles around the deeper question of what marriage is actually for. Like Liars by Sarah Manguso, it questions if women can ever be psychologically liberated within a marriage, but it does not question the fundamental underpinnings of marriage as an institution. July sees sexual exploration as a way out of her stale and traditional life. Manguso sees her future potential sex life as destructive and patriarchal, another dead end.

In Liars, Jane, whose husband has pressured her into the role of a stay at home mother, ostensibly in support of her writing career, finds out that he is having a secret affair with a friend of his. Although she started dating her husband before he was fully out of his last relationship, and although he smeared his ex-girlfriend as crazy, she is blindsided by this pattern when it resurfaces. She is able to see the profound inequality in her own relationship, how her husband forced her to shrink intellectually, how he stigmatized her as emotionally hysterical, how he isolated her and made her financially dependent, and she connects her marriage abstractly to a long lineage of mistreated women. But she is unable to really empathize with most of the other women who appear in the book or to see their experiences as interwoven. She only apologizes to the girlfriend her husband left her for after he has abandoned her in turn. The babysitter she fights to hire in order to shoulder some of her reproductive labor is nameless and faceless, a silent woman who tends to her child. And her husband’s affair partner, Victoria, is portrayed as an oversexed homewrecker, both calculating and naive, blissfully unconcerned with her own family. Jane tells the shocked mediator early on in her divorce proceedings that Victoria has abandoned her children for her own gratification. During a tense email exchange with her husband in the same period, she pictures Victoria sitting on the couch next to him, coaching him on what to say in her “slimy panties.”

Liars is resolutely fatalistic. Jane marries her husband in the first place because she feels herself on the cusp of aging out of the dating market. Marriage is an inevitability in the novel and its unhappiness is equally inevitable. All heterosexual relationships are enclosed in this cage of suburban isolation and domestic submissiveness. When Jane herself experiences a flicker of sexual desire after her divorce, she sees it as a horrifying confirmation of her servitude to what she deems emotional labor. “When an entire civilization tells you that you owe that cock a good suck and fuck, it isn’t a personal failure when you give in. You’ve been coerced.” Wanting sex is an embarrassing biological impulse; it resigns you to abject womanhood.

Liars wrestles with at times with the inherent difficulty in writing about a process of victimization. To understand yourself as a victim of another person or of an experience is to understand yourself as acted upon, as passive. Narrative fiction on the other hand demands agency at its core and not passivity. Manguso wrote the book, according to interviews she has done, in the heat of betrayal, while she was going through a divorce with her own husband who had cheated on her. In the book, the wife is wronged, virtuous, endlessly patient. It is tempting to wonder how differently it might have turned out if Manguso had waited five or ten years to write it.

July also separated from her husband recently. She announced in July 2022 that she and the filmmaker Mike Mills were no longer romantically involved, although they continued to share a house and co-parent, and that they were each dating other people, much like the couple in All Fours. Rachel Cusk likewise publicly separated from her husband, a photographer, and published a divorce memoir the next year. Perhaps this is why all three books feel similarly undernourished, the result of personal upheaval more than anything else. All three see marriage above all as a personal problem and divorce as a compounding problem. They worry about maintaining their respectability, their attractiveness, their wealth. They worry about ending up as the untidy women of Ernaux’s youth, women who are ultimately perhaps defined less by their gender and more by their position in life.

Ernaux often writes looking backwards, mixing her current knowledge with her past consciousness. In A Frozen Woman, published when she was nearing 40, she too worries about ending up old and unsexed. By her later work, she is more interested in the ephemerality of pleasure, in the power of tenderness, in the distance that exists between her past and present after decades of rising up the social ladder.

In The Uses of Photography, her most recent book to appear in English (the original was published in 2005), she describes a relationship she had while she was undergoing treatment for breast cancer. When she and her lover have sex, her medicalized aging body, made hairless by chemotherapy and fitted with a pump near her armpit, becomes something beautiful and desirable, a vehicle for her own pleasure in the face of her suffering. Her lover calls her his “mermaid-woman” because of her sleek hairlessness. When she sees elderly women in the supermarket, instead of experiencing her youthful fear of wrinkling, she now feels a sad certainty that she will die before she ever reaches old age.

She and her lover start a ritual where they photograph their clothes strewn on the floor after sex, their unmade bed, their coffee cups. In the book, she describes the relationship in hindsight, and her relationships with men more broadly, as a way of acquiring knowledge. Through these encounters, she learns how to differentiate herself, her wishes, her desires, her intimacy, the boundaries of her self.

Towards the end of the book, she writes a short essay to accompany a photograph of her bed. This bed, she explains, was one she bought with her husband. They looked high and low for it because they wanted it to look like Brigitte Bardot’s. They ended up ordering a custom one and by the time it came, they had stopped having sex. Three years later they broke up. The bed is reinvented here, no longer a symbol of bourgeois marriage, of tidiness and chastity and devotion. Instead, it is a symbol of her self-determination and of her rejection of the wifely role she chased for so long. She does not view her divorce as a failure. Rather, it is her marriage that was an incongruous misstep in the first place.

As you have seen from this post, I have decided to move my newsletter back to Substack. This is mainly logistical: the other platform where it was hosted has a limit on the number of subscribers for a free account. Paying for an account would have made it financially impossible for me to keep this newsletter free. I still intend to primarily send out free essays. I am grateful to everyone who has continued to financially support me here and you are welcome to choose a paid subscription starting at $5 if you would like to offer support.

I love how you tied all the books together, a masterclass in synthesis! I’ve gotten to see a couple of my friends from dating to marriage, and had the bleak realization that the health of their marriages was dependent on their individual economic standing, more than anything. My coworker and I also broke down a couple of the married couples he knew and it always comes down to class contempt. I don’t know how you straddle the line between realism and romanticism so well.. the more I think about how fidgety and sooceconomic-based love is the more I despair…

This is a great read, thanks for writing. The only note I'd give around July's novel is that her main character is an artist like July herself, and the way her powerful id drives her creative life resonates with me. I haven't laughed that much reading fiction in a long, long time.