Negative options

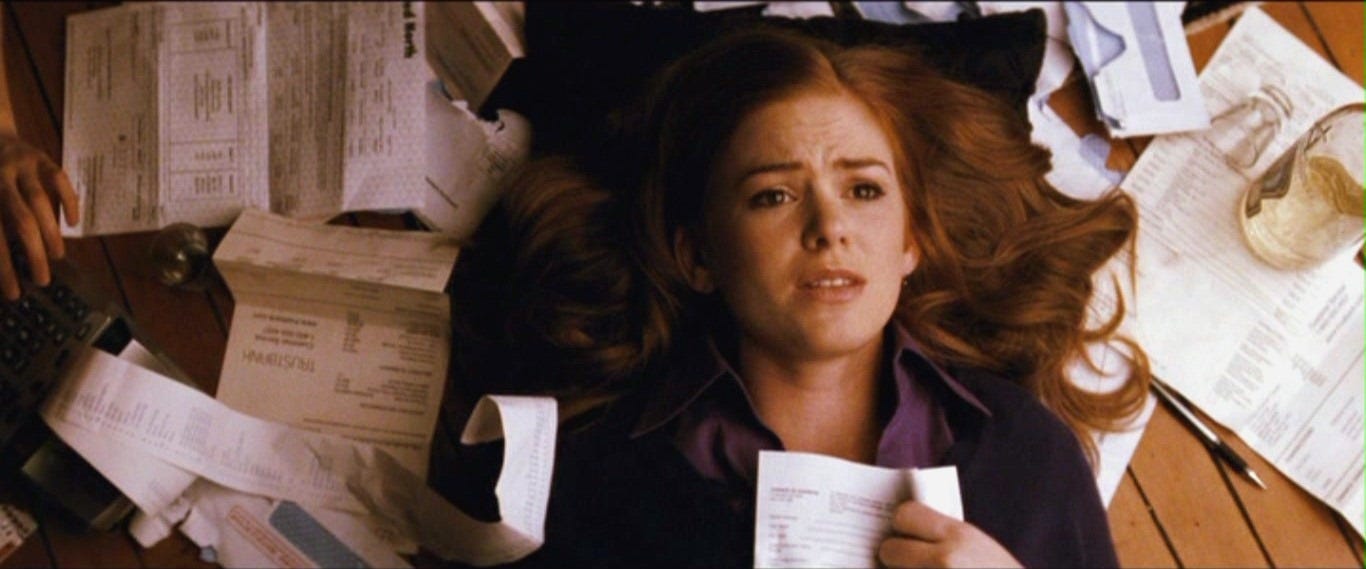

There is a scene in the underrated 2000s rom com Confessions of a Shopaholic where the titular shopaholic, Rebecca Bloomwood, squints at a credit card bill (mailed to her at work in paper form), trying to figure out how she spent so much money. Finally, she spins her chair around happily to declare that somebody has stolen her credit card. “I’ve never been to Outdoor World,” she explains. “I’ve never even seen a tent.” Her coworker helpfully intervenes to let her know that she has, in fact, been to Outdoor World to purchase a collective going away gift for a former colleague. No arguing with such infallible logic. Later on, in an implausible series of twists, Rebecca becomes a financial advice columnist.

I only look at my credit card statement when I am alone. It is an agonizing activity. I always, like Rebecca, cycle through disbelief, looking for proof that my card has been stolen. It never has been. But more and more, as I scroll through my statement, I do find evidence that I am being defrauded. There are indeed charges on my bank account that I did not authorize. But instead of someone else’s shopping spree, they are something more insidious: recurring charges.

It is notoriously difficult to cancel a subscription right now. Lina Khan, when she was chair of the FTC, passed new regulations about it last year, specifically targeting “negative option” features. In other words, tools by which a company will enroll you in a paid subscription without your explicit consent or proceed automatically from a free trial to a paid subscription if you do not take any action. Apparently, the volume of complaints the FTC was receiving about this had nearly doubled between 2021 and 2024. With all due respect to Lina Khan, these new regulations do not seem to have had any effect.

Some of these recurrent charges are egregious. I canceled my ClassPass account in November 2024, mainly because they had steadily increased the number of credits required to take a class each month, trying, I assume, to goad me into upping my membership level. They started billing me again, I recently discovered, in February. There is no apparent impetus for this. In a truly shocking Reddit thread I read about ClassPass’s shady business practices, the poster claimed they realized after *18 months* that there were unauthorized charges on their account and reached out to ClassPass for an explanation. ClassPass responded explaining that another account shared the same payment method as this user and due to privacy laws, they could not disclose who this other person was and so could not stop charging the card.

This obviously is why you must look at your credit card statement and more often than once every 18 months. I have attempted unsuccessfully in the past few months to cancel subscriptions from Paramount+ (the home of Couple’s Therapy), a scammy resume builder website I used (I probably get what I deserve for that), and Google Workspace, which I purchased through an email address that Google immediately afterwards locked me out of for the better part of a year. They continued to charge me for Workspace though. When they finally gave me my access back, it still proved nearly impossible to cancel my Workspace subscription. You cannot do it on a mobile phone. When I tried to do it on my computer, it demanded 2 step verification from the Gmail app on my phone. When I tried to log into this email account on the Gmail app, it demanded the same 2 step verification process, which was impossible, given that I was already using the phone app. I have also been charged by a Telehealth company which promised me in writing a $200 refund I have yet to receive for months where they inexplicably halted my prescription. I recently discovered I somehow had a Mubi subscription I do not recall ever signing up for. My mother, who grudgingly pays for Netflix, has not been able to access her account for weeks if not months since Netflix claims she is logged in on another device. They will not tell her where the device is located or how to log out of it.

As the manager of a business, I think I can say with confidence that this is a totally inexplicable way of running a business to me. I assume it is not all sheer dishonesty, but some part incompetence, a slashing of customer service jobs and replacing them with AI or emails that lead nowhere. Companies seem to be black holes. No one on the bottom, you can assume, really knows what is going on. The information you are seeking is mystified and out of reach. Adlan Jackson wrote at length in Hell Gate about trying to get OMNY (New York’s new contactless transit payment system contractor) to let him update the expired card on his account. I refuse to use OMNY for this reason, although sometimes when I swipe my outré metro card, the OMNY system detects my phone in my pocket or purse and charges it anyway. I cannot dispute these charges because my bank told me I would have to call OMNY and I do not have the fortitude to wait on hold for hours over two dollars and ninety cents.

I am fully aware it can be worse. I once had my bank account frozen because I moved money around too much and JP Morgan suspected me of money laundering (they later apologized for this). Charlotte Cowles, the Cut’s financial advice columnist (and a Rebecca Bloomwood if there ever was one), wrote a viral article about falling for an Amazon scam and paying out $50,000 in cash to a man in a white Mercedes who claimed to be in the CIA. Reader, he was not. Large-scale, life-ruining scams seem to be popping up everywhere, targeting the elderly, the technologically illiterate, the vulnerable, the poor.

The low-level grifting of ClassPass or Google Workspace or my Telehealth company are obviously not at this level. But what it does offer is a roadmap to what everything is going to be like very shortly. Bill Gates claimed in February that in 20 years AI will replace teachers, doctors, and mental health professionals. This is obviously preposterous. But it provides a kind of logic for the precipitous decline of basically everything, how easy it is to gut things that basically function and turn them into slop that can be ravaged over by private equity companies. Examples are everywhere: the Trump administration used a formulation that was apparently calculated in Chat GPT to set their now suspended tariff rates; Andrew Cuomo used Chat GPT to write part of his incoherent 29 page housing plan and left the citation in (he blames an “aide” for this); Duolingo started laying off translators en masse last year to rely on AI for its language lessons. The phrases I was offered last time I used the app included garden variety sexism and fatphobia.

This slash and burn approach has characterized the first few months of DOGE, the new semi-governmental agency tasked with destroying the government. Elon Musk and other members of the administration have repeatedly made false claims about social security fraud, based on algorithmic “find on this page” kind of data. (These include flagging multiple different benefits paid out to people as fraudulent duplicates and claiming children receiving social security benefits for dead parents were committing fraud). It is easy to dismiss this as sheer incompetence and it certainly is that. But it is also real, unmitigated contempt for the population, who are all cast as unwilling consumers in this mode of operation, swimming upwards in a choked river of corporate fraud, malfeasance, pollution, poison, and theft.

In this grifter era, we are governed by the logic of government-as-corporation that owes you nothing and that can bully, defraud, and terrorize you as it pleases. If you, the consumer, do not like it, you cannot opt out. There is nowhere else to go. In Atlas of AI, Kate Crawford counters the idea that human workers will be widely “replaced” by robots by asserting that humans are increasingly treated like robots already under the influence of productivity algorithms, surveillance tools, and other technological data metric systems. “Rather than representing a radical shift from established forms of work, the encroachment of AI into the workplace should properly be understood as a return to older practices of industrial labor exploitation that were well established in the 1900s and the early twentieth century.” This is the meaning of industrial capitalism, subsuming workers to a rhythm and logic of mechanical productivity that destroys their minds, bodies, and communities, and that often makes for worse work all around. Crawford describes how many seemingly automated systems have simply rerouted labor, forcing humans to do endless repetitive back-end tasks to update and maintain them. If a future of increasing automatization offers us anything, it is undoubtedly this.

In this context, it is hard to say if the proliferation of uncancellable subscriptions is really because of increasingly hubristic attempts to hustle people out of their money or if it is simply the result of rapidly multiplying errors in systems that are under-maintained, require manual data entry work, and are not designed to function in service of customers. All this seeming automation really does is render low-wage labor invisible to the consumer.

I rewatched Confessions of a Shopaholic recently for the first time I think since I was a teenager. So much of it was burned into my memory and I still found Isla Fisher charming in it, the irresistible allure of mannequins waving at her from store windows, her belief that inevitably she will find a way through her disastrous life, her meteoric rise to journalistic success after seemingly writing one single column, and her disgust at the creepy, nefarious debt collector who hounds her. But it was strange to consider that the film was released in 2009, at the height of a recession. Its feel-good ending (Rebecca pays off her debt through a yard sale) and lavish materialism were greeted as in poor taste at its release. Undoubtedly, they are, but what struck me as tasteless, plunging into a new recession, was more its bootstraps messaging; the idea, implicit throughout, that if Rebecca, a journalist at a series of low-rent magazines, just managed her money well and worked hard, she too could buy a house, that credit card debt is just a personal problem you get from buying too many shoes, that there is no overarching flaw in this system.

In the most uncomfortable scene in the film, Rebecca goes to see her parents, planning to ask them for a loan to help pay her ballooning debt. Her parents have their own announcement to make: they have taken all the money they saved while making good financial choices their whole lives and bought an RV. Rebecca feels too guilty to blame them. She assumes by the end when she has miraculously fixed her finances that she too will grow old, make good choices, and splurge on an RV. Little does she know what is coming for her. It is 2009, the billionaire playboy funded finance magazine she goes to work for will probably soon shutter, the apartment she slums in will soon charge skyrocketing rent, her life has been foreclosed.

You put it perfectly into words I have not had until now, how we are being treated like consumers of a business but we're the people residing in a country..!! Thank you for that, I will argue a lot better now!

Also, the best way to get out of reoccurring charges is to change your credit card number! I've called the bank on one of those resume builder website charges as fraud, got my money back and then they mailed me a new card! Fuck that shit yk?

This sort of thing is infuriating. Another layer of aggravation is that a few times now I've had to help out older members of my family who aren't as tech savvy with this sort of thing. A dull tedious grind that wouldn't be allowed to exist in even a fractionally better world.